Kalshi’s Nevada court victory faces legal hurdles amid federal sports betting bans

A recent court win by prediction market operator Kalshi in Nevada may be short-lived, as unresolved federal legal challenges—particularly the Wire Act and CFTC regulations—threaten to upend the ruling.

A federal judge in Nevada last week issued a preliminary injunction shielding Kalshi from state-level enforcement, holding that Kalshi’s “sports-based” event contracts are permissible under federal law—“at this point in time.”

The court found that Kalshi’s operations fall under a “special rule” created in the 2010 amendment to the Commodity Exchange Act (CEA), allowing designated contract markets (DCMs) to self-certify event contracts without prior approval from the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC).

Because Kalshi is a CFTC-regulated exchange, the court ruled that state gambling laws are “field preempted.” The judge concluded: “Federal law allows Kalshi to offer... sports... contracts on its exchange.”

However, legal analyst Daniel Wallach warned in a Forbes article that the decision could unravel as federal statutes that explicitly prohibit sports gambling were not addressed in court filings—most notably the Wire Act of 1961, which prohibits the use of interstate wire communications for transmitting sports wagers. Also absent from Nevada’s argument was CFTC Rule 40.11(a)(1), which bans event contracts that involve or reference “gaming” or any activity that is illegal under federal or state law.

Acting CFTC Chair Caroline Pham said, "There is no further public interest test in Rule 40.11(a)(1),” underscoring that contracts tied to illegal activity are automatically barred. Kalshi itself has acknowledged in past litigation that “if trading a contract violated a ‘federal’ law, that instrument would be banned regardless of the Special Rule.”

The omission of these legal angles has drawn criticism. “The Nevada Attorney General never raised [the Wire Act],” noted one commentator, suggesting that the court relied too heavily on procedural compliance while overlooking the broader legal framework.

Concerns over the CFTC’s ability to oversee sports betting markets are also mounting. In a recent letter, Major League Baseball said “those protections are lacking” when it comes to event-based sports contracts. The league added: “MLB is not aware of anything that would require exchanges and brokers to notify leagues of potential threats to game integrity.”

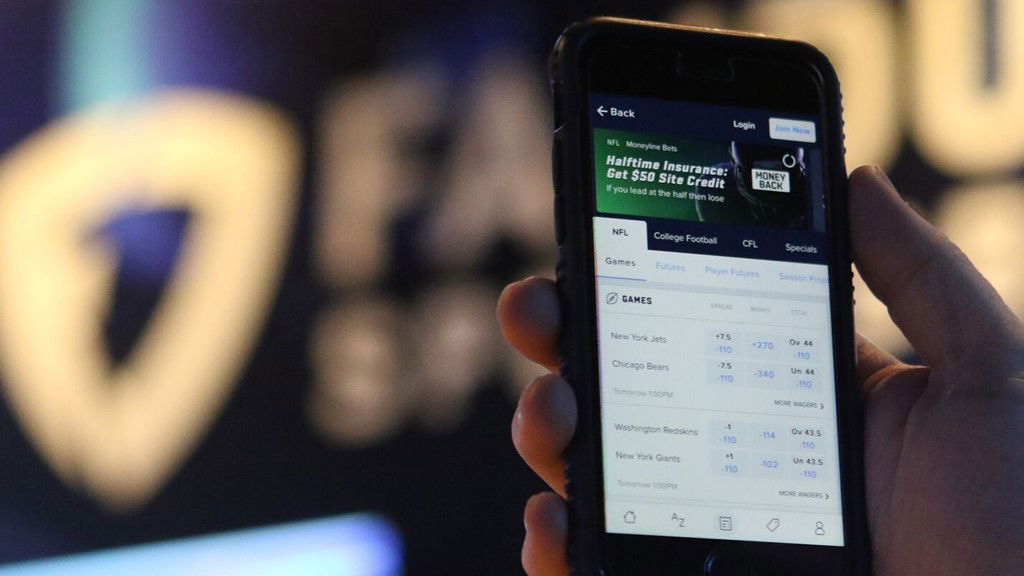

Kalshi’s model—described as a peer-to-peer “financial exchange”—has been criticized as a distinction without a difference from traditional sportsbooks. Critics point to federal precedent, including the First Circuit’s ruling in New Hampshire Lottery Commission v. Barr, confirming that the Wire Act applies to internet-based sports betting.

Nevada may still have a chance to challenge the ruling. The state’s official response is due April 23, with a status hearing scheduled for April 30. The court notably left the door open for reconsideration, stating only that Kalshi’s contracts are permissible “at this point in time.”

Legal experts suggest that Nevada could reintroduce the Wire Act and Rule 40.11(a)(1) as grounds for invalidating Kalshi’s sports contracts. The state might also invoke Kalshi’s own prior admissions, including its assertion to the D.C. Circuit that “Congress did not want sports betting to be conducted on derivatives markets.”

Given Congress’s historically explicit approach to regulating sports gambling—through statutes like PASPA and the Wire Act—critics say the idea that it would legalize federally regulated sports betting by implication defies decades of legislative precedent.

When Congress decides to tackle sports gambling, it does so directly and openly, as highlighted by a commentary referencing a 1991 Senate Judiciary Committee statement that described sports gambling as a nationwide issue.