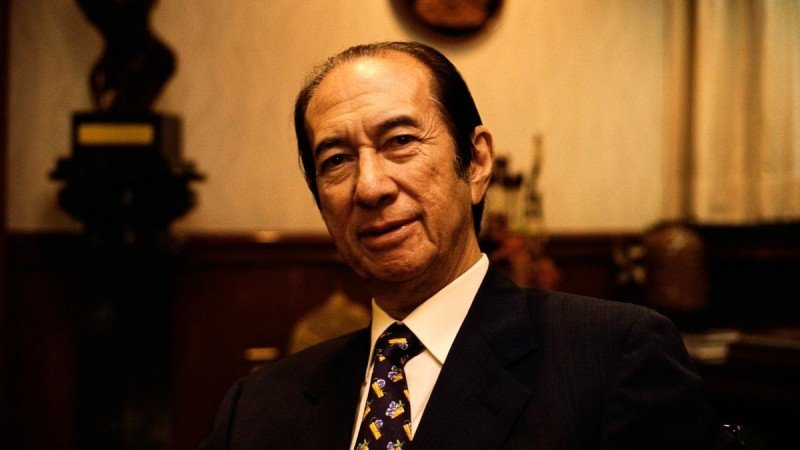

Macau casino tycoon Stanley Ho dies aged 98

Stanley Ho, who steered gaming in the autonomous Chinese region to eclipse Las Vegas, has died in Hong Kong aged 98.

Ho was also a philanthropist and construction magnate whose business empire spanned the globe, including investments in North Korea.

"My father has passed away peacefully just now at around 1 pm at Hong Kong Sanatorium and hospital," said Pansy Ho, one of his daughters. "As Stanley Ho’s family member, we are really sad to inform you of this."

With 20 casinos under his control in Macau, the only Chinese territory where such businesses are allowed, he was credited with bringing in about half the region’s tax receipts via the “Las Vegas of Asia” and was personally worth almost $7bn (£5.7bn), only retiring aged 96, the Guardian reports.

He leaves 14 surviving children he fathered with four wives. During his later years his extended family engaged in high-profile squabbles over his empire.

Ho built up the gaming industry in Macau under a monopoly license until 2002, when the arrival of foreign investors sparked a boom which resulted in casino takings contributing to about 80% of its annual revenue and overtaking Las Vegas.

Born in 1921 in Hong Kong into a wealthy and politically well-connected Eurasian family which had made money from the British trading company Jardine Matheson, the family fell on hard times during the Great Depression in the mid-1920s, before the impoverished Ho fled to neutral Macau – then a Portuguese colony – during the second world war.

"I was a very poor man," Ho told Reuters in an interview about his arrival in Macau with the few dollars he had earned working with the air raid administration in the week before Hong Kong’s capture by the Japanese. "I started with only HK$10. That was my capital."

It was there, however, that Ho would make his first fortune before the age of 24, smuggling goods into China while collaborating with the Japanese, before establishing himself as one of the players in Hong Kong’s postwar reconstruction.

By 1961, he was well enough established to secure the monopoly for Macau’s new legal gambling franchise that would propel him to stellar riches and prospered even after the region returned to Chinese control in 1999.

Recognizing that he needed to attract high-rollers from Hong Kong, Ho built a harbor to accommodate the high-speed boats that would ferry Hong Kong gamblers to his casino hotels.

As reported by the Guardian, he would only lose his monopoly when it was opened after four decades to wider competition including from the US billionaire Sheldon Adelson’s Sands China.

Ho’s Sociedade de Jogos de Macau Holdings (SJM) empire remains a major player in Macau. The company took a hit alongside its competitors after China’s president, Xi Jinping, launched a high-profile corruption crackdown in 2013, triggering a dramatic decline in high-rollers visiting Macau.

Allegations of Ho’s connections to organized crime, including from US regulators, dogged him for years, most recently in Australia where the New South Wales gaming authority last year launched a public inquiry into his son Lawrence’s purchase of a 19.9% stake in Crown Resorts from James Packer.

In 2010, after a long investigation, the New Jersey gaming authorities issued a report declaring a link between Ho and the triads and requiring that MGM Mirage Macau (a joint venture with Ho) divest its interest in an Atlantic City casino.

The 74-page report said Ho was an associate of known and suspected triads who had permitted "organized crime to operate and thrive within his casinos".

In particular law enforcement officials suspected his casinos’ VIP rooms were used by triads to launder money, a claim put to Ho by the New York Times in 2007. Ho did not deny the allegations but said that during the 1980s and 1990s “anyone involved in gaming was vulnerable to such accusations”.

His last years, however, would be marked by illness and infighting among the factions in his sprawling family. After a fall at his home in 2009, after which he had brain surgery, his family was riven by a bitter dispute resolved two years later when his gambling business passed to his daughter Daisy.